Floodline

How the Great Flood of 1937 brought two Kentuckians — and the family that followed — to higher ground.

Before the water came, before the city turned to river, before a man rowed through a drowned street to reach the woman he’d only just met — there was Aunt Mag.

Anna Margaret Whelan Thomas had a romantic streak. She believed in timing, in fate, and in paying attention to the things other people missed. Working at Fontaine Ferry Amusement Park in the mid-1930s, she worked a ride and kept a watchful eye on her coworkers. One in particular stood out.

Mary Lee Zweydoff was graceful in a way that didn’t draw attention to herself. Friendly, poised, and always composed, she had inherited her mother's German cheekbones and her father's charm. She was the eldest daughter in a sprawling Catholic family of ten siblings. Born in the Portland neighborhood of Louisville on August 23, 1919, she’d grown up among the flatboats and floodplains, the clang of steamboat bells, and the hush of family stories told in kitchens over weak coffee and strong memories.

Her name — Mary Lee — was a bridge between two pasts. “Mary” for her maternal grandmother, Mary Louisa Rolfes, who died before she was born. “Lee” for her paternal grandfather, Lee Zweydoff, whose name, passed down, was a whisper of older worlds: of Germany, of hardship, of a family that had long since made the Ohio River home.

Mag liked her immediately. But more than that — she saw something. She thought of her nephew: Wilbur Padgett, born on a Meade County farm on November 7, 1915. He was the second-oldest son of twelve, raised at the meeting point of Otter Creek and Dry Branch, where the land folded into itself and boys became men early. He had callused hands, a work-worn back, and eyes the color of Kentucky limestone under morning light.

Handsome, yes — but it wasn’t that. It was something steadier. Something you could trust.

“They both had pretty eyes,” Mag would say later. “And I thought they’d make a good match.”

So she made the match.

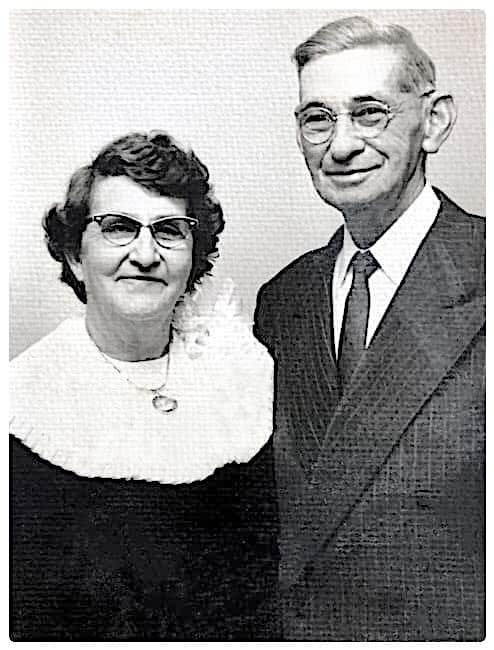

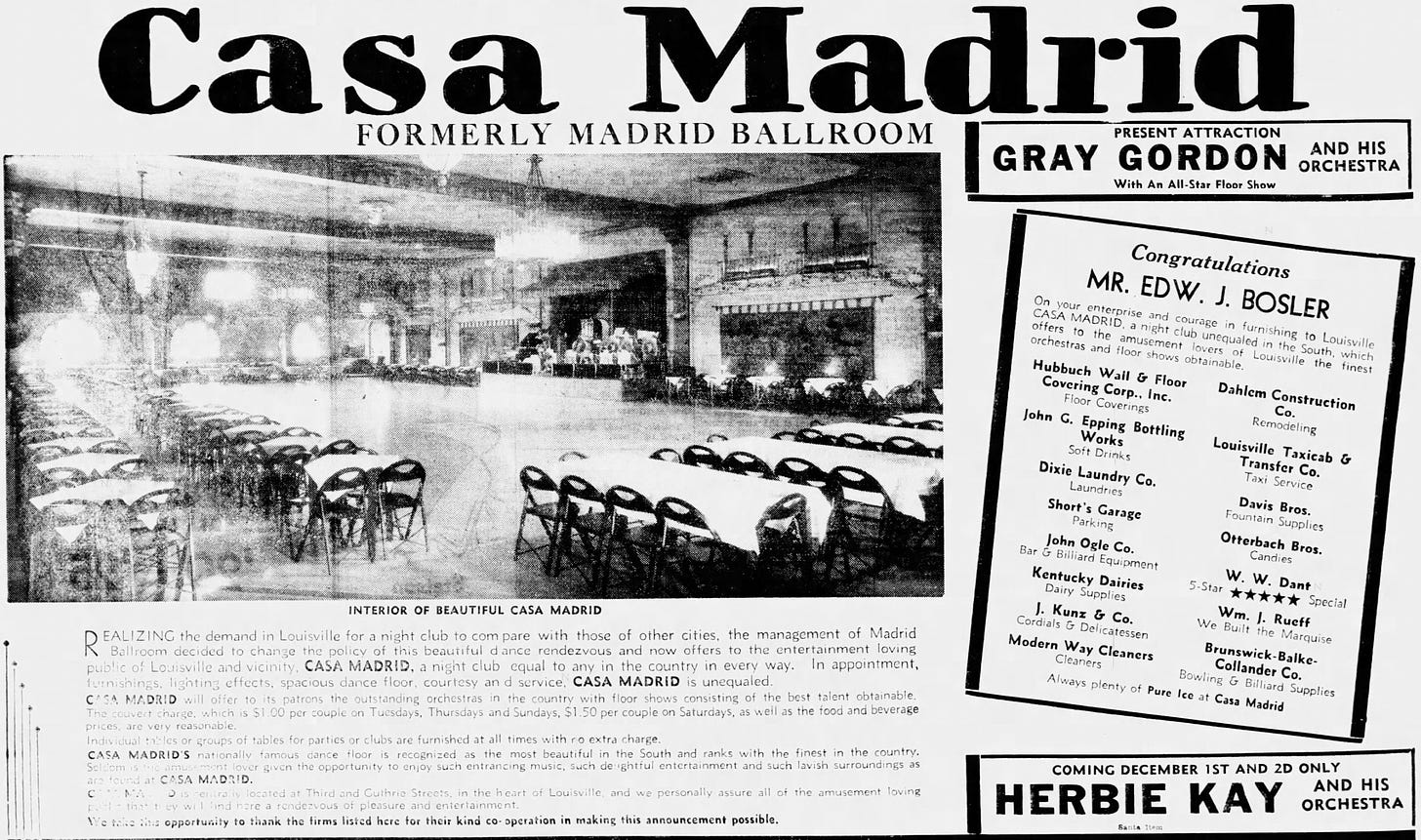

The blind date was set for New Year’s Day, 1937 — a holiday dance at the Casa Madrid Ballroom on Third and Guthrie. It was a night for pressed suits, polished shoes, and jazz slow enough to sway to. Mary Lee wore a simple dress and her favorite necklace. Wilbur stood tall in a well-fitted suit, sharp as ever. He dressed the way he carried himself — with quiet pride and intention.

They danced. Talked. She liked his quiet confidence. He liked the way her gaze held his without hesitation.

“He was a very good dancer,” Mary Lee would say decades later. “And he had really pretty eyes.”

They agreed to see each other again.

But life — and the Ohio River — had other plans.

The rains began almost immediately after their first meeting. A slow, persistent drizzle at first. Then a downpour. Day after day, the skies refused to clear. In Louisville, January 1937 brought twenty-three straight days of rain. The Ohio River, already swollen from a wet winter, surged. Creeks spilled their banks. The city’s stormwater systems failed. And then the river turned on the city.

Flood stage came and went. By the third week of January, the water had risen more than 30 feet above normal. On January 27, the Ohio crested at 52.15 feet — an unprecedented high. Seventy percent of Louisville lay underwater. Streetcars were stranded. Telephone lines snapped. Gas and electric services failed. Thousands fled, their belongings bundled on their backs.

Slevin Street, in the Portland neighborhood where Mary Lee’s family lived, was no exception.

The water came slowly, lapping at doorsteps like a visitor unsure whether to come in. Then it rose, relentless, swallowing sidewalks, porches, and parlors. The Zweydoff family tried to wait it out, but there was no end in sight. They needed to evacuate.

And that’s when Mary Lee sent word to Wilbur.

She didn’t ask him to come. She only told him what was happening. That was all he needed.

Wilbur found a canoe.

No one remembers where it came from — if it was borrowed, found, or fashioned. What’s remembered is what he did with it.

He paddled across streets that no longer had names, only currents. Past telephone poles that looked like river markers. Past drowned storefronts and submerged curbs. The city was eerily quiet, the way it gets after disaster takes the noise with it.

And then — there they were. The Zweydoffs, waiting on what remained of their front porch.

“When I saw his crystal blue eyes in the canoe that day,” Mary Lee said later, “I knew I wanted to be with him the rest of my life.”

He ferried them to safety — Mary Lee, her parents, her siblings. They stayed with relatives elsewhere in the city until the waters receded.

Sometimes, love doesn’t arrive with roses. Sometimes, it rows.

The flood took everything. More than 175,000 Louisvillians were displaced. Damages totaled what today would be over a billion dollars. It would take decades to construct the 29-mile floodwall system the city now depends on.

But amid all that ruin, something else was built — quietly, and without blueprint.

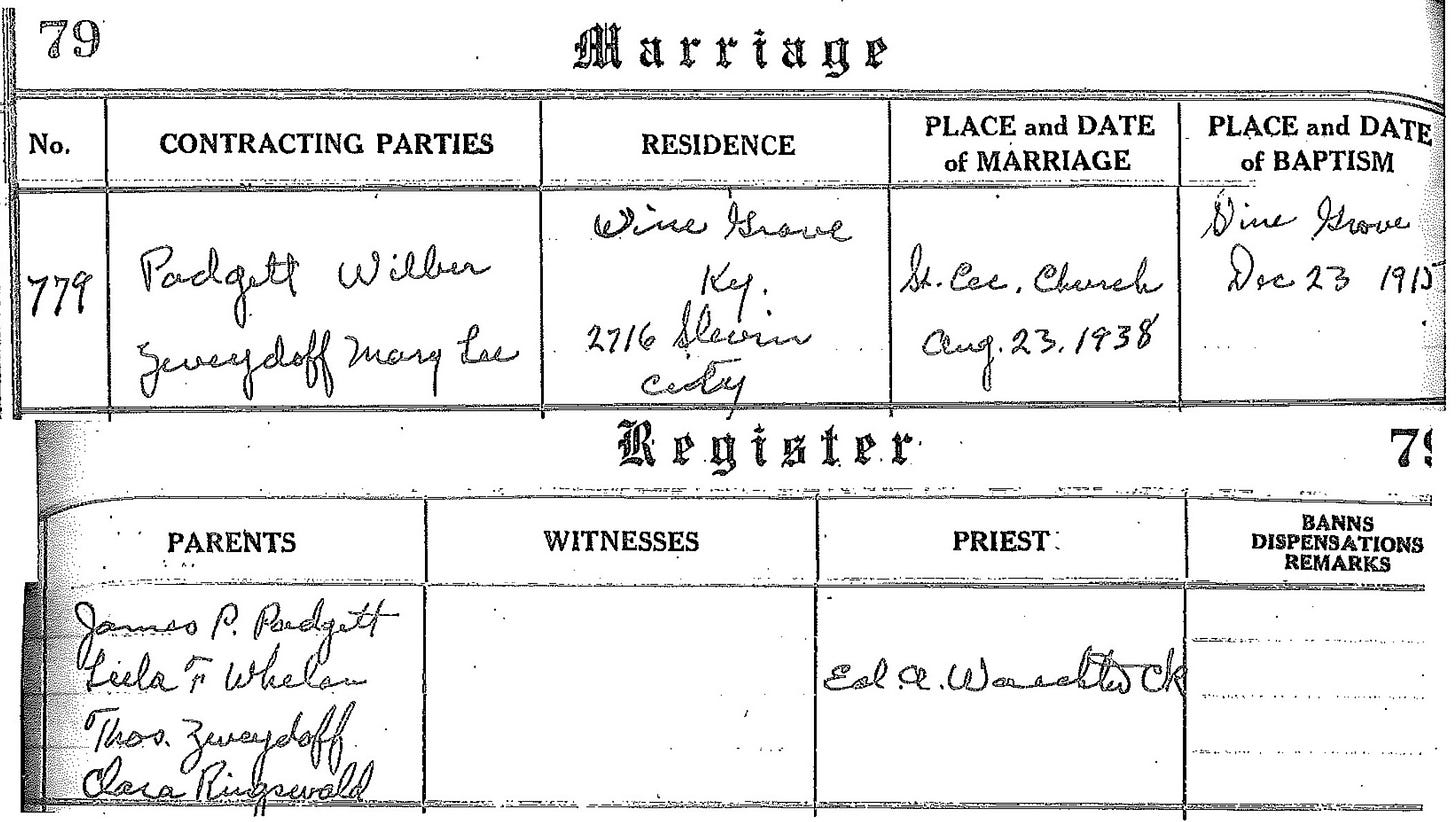

When spring came, Wilbur proposed. And on August 23, 1938 — Mary Lee’s 19th birthday — they were married at Saint Cecilia Catholic Church in Portland, where her parents had wed before her.

There was no spectacle. Just two families, four witnesses, and two hearts that had already known what it meant to endure.

They made a life together.

Eleven children. A house full of noise, faith, and motion. Wilbur spent most of his career as a supervisor for Armour-Klarer, a Louisville-based meat processing company owned by the Broecker family. He worked with steadiness and integrity, earning respect not just for what he did, but how he did it. Mary Lee anchored the home. The family grew. Years passed. A flood of a different kind — children, then grandchildren, then great-grandchildren — followed.

Wilbur and Mary Lee would be married for 48 years, until his untimely death in 1986. Mary Lee lived on for another 25 years — steady, strong, and surrounded by the family they built — until her passing in 2011. But the life they made together never stopped growing. Today, their descendants number seventy-six.

And Aunt Mag?

Her story came back to me decades later.

In 2011, I joined the Downtown Louisville Rotary Club. At a welcome dinner for new members, I found myself seated next to another new member named Steven Schmidt. We struck up a conversation — the kind of easy back-and-forth that happens when two people share a city, a history, a way of speaking.

At one point, he mentioned his grandmother.

“Her name was Anna,” he said. “Anna Margaret Thomas.”

Something stirred.

“Whelan?” I asked.

He smiled. “Yes. Anna Margaret Whelan Thomas.”

Aunt Mag.

I paused, then smiled. “You may not know this,” I told him, “but your grandmother set up my grandparents on a blind date in 1937. She thought they both had pretty eyes. And had she not played matchmaker, I wouldn’t be sitting here — or telling you this story.”

Steven was quiet for a moment, visibly moved. He’d never heard the story before. “I had no idea,” he said. “That’s incredible.” He told me how meaningful it was to learn that his grandmother’s quiet instinct had helped shape another branch of the family tree — one he hadn’t known he was connected to.

It was a full-circle moment. The story of the canoe, the dance, the flood, and the family that followed — it had been told to me many times over the years by my grandmother. And in every telling, Aunt Mag’s name carried weight. She wasn’t just remembered. She was revered.

In that moment, the circle closed. The woman who had sparked my grandparents’ story had a grandson sitting beside me, in the same city, at the same table, decades after her quiet act of matchmaking changed the shape of a family.

Sometimes, the past doesn’t feel so far away.

Sometimes, the people who changed everything leave ripples that never stop reaching.

Floods come.

They rise, destroy, and remake.

They erase old paths — and carve new ones.

Louisville knows this all too well.

The city just weathered another historic flood — one of the worst in its recorded history.

And as the waters crept up again,

so did the memories of 1937,

when a boy in a canoe paddled through the city not to flee — but to find someone.

Mary Lee and Wilbur met on dry ground,

but it was the rising water that showed them who they truly were.

Not swept away — but carried forward.

He came for her in a canoe.

She saw him and knew.

And from that moment on,

the river was no longer something to fear.

It was the current that began a family —

guided first by love, and just a little by Aunt Mag.

Their love still traces the shape of the floodline.

And even now,

their story carries us all toward higher ground.

Notes Behind the Story

The Great Flood of 1937

Louisville Metropolitan Sewer District, “Floodwall History and Facts,”https://louisvillemsd.org

National Weather Service, “The Great Flood of 1937”

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Ohio River Flood History Archives

Courier-Journal archival reporting, January–February 1937

Mary Lee Zweydorf and Wilbur Anthony Padgett

Oral history interview with Mary Lee Zweydorf Padgett, March 1990

Padgett Family Archive: family photographs, wedding records, and written reminiscences

Marriage Record, St. Cecilia Catholic Church, Louisville, Kentucky, 1938

Obituary of Wilbur Anthony Padgett, Louisville Courier-Journal, 1986

Obituary of Mary Lee Zweydorf Padgett, Louisville Courier-Journal, 2012

Anna Margaret Whelan Thomas (“Aunt Mag”)

Marriage Record: Anna Margaret Whelan and James Kelly Thomas, Vine Grove, Kentucky, November 12, 1912

Family records shared by descendants, including Steven Schmidt (2011–2018)

Personal conversation between author and Steven Schmidt, Downtown Louisville Rotary Club Welcome Dinner at Vincenzo’s Restaurant, 2011

Contextual Material

Jefferson County Floodplain History Map Layer (Louisville/Metro GIS Consortium)

Casa Madrid Ballroom: Louisville Dance Halls, University of Louisville Archives; Courier-Journal

U.S. Census Records, Portland Neighborhood Enumeration, 1920–1950

History of Armour-Klarer Company - Broecker Family website www.broeckerfamily.com

What a wonderful story and storytelling! Those full circle moment s are so rare and precious when they come - thanks for sharing this one.

Precious. Thank you. What a gift.